GRASS IS GREEN

docu-fiction with the question _Why to rinse a plastic yoghurt cup if my neighbour flies to Thailand four times a year

photo Ctibor Bachratý

concept, direction, texts: Petra Fornayová

cast: Vlado Zboroň, Silvia Sviteková, Petra Fornayová

in videos: Marinko Pintar, Lazi Drago

dramaturgy: Peter Šulej

media, sound, technical direction: Fero Király, Jakub Pišek

scenography: Matej Gavula

video and editing: Adam Hanuljak, Jakub Pišek

production: Contemporary Dance Association / Tereza Michalová, Association Divadelná Nitra / Anna Šimončičová

co-producers: Association Divadelná Nitra (SK), Contemporary Dance Association (SK), Dublin Theatre Festival (IE), Kunstencentrum Buda (BE), Plesni Teater Ljubljana (SE)

Realized in the framework of the European project Be SpectACTive! – Associazione Culturale CapoTrave / Kilowatt (IT), Artemrede – Teatros Associados (PT), Bakelit Multi Art Center (HU), Koproduktionshaus Wien / Brut (AT), Kunstencentrum Buda (BE), Café de las Artes Teatro (ES), Domino Udruge (HR), Asociácia Divadelná Nitra (SK), Dublin Theatre Festival Company (IE), Göteborgs Kommun – Göteborgs Stads kulturförvaltning / Stora Teatern (SE), Institution Student Cultural Centre (RS), Occitanie en scène, Réseau en scène Languedoc-Roussillon (FR), Plesni Teater Ljubljana (SI), Tanec Praha (CZ), Teatrul Naţional Radu Stanca Sibiu (RO), Fondazione Fitzcarraldo (IT), Universitat de Barcelona (ES), Université de Montpellier (FR), Centre national de la recherche scientifique / CNRS (FR).

Supported by the Creative Europe programme of the European Union.

Supported from public funds by the Slovak Arts Council.

Other project partners: Deputy Prime Minister’s Office for Investments and Informatization, City of Nitra, Nitra Self-Governing Region, Flanders – State of the Art, SPP Foundation, LITA – Society of Authors, Bratislava Self-Governing Region, City of Bratislava Foundation

Special thanks: Katja Somrak, Urša Adamič, Martina Vannayová, Mateja Koren, Beáta Kolbašovská, Primož Repar

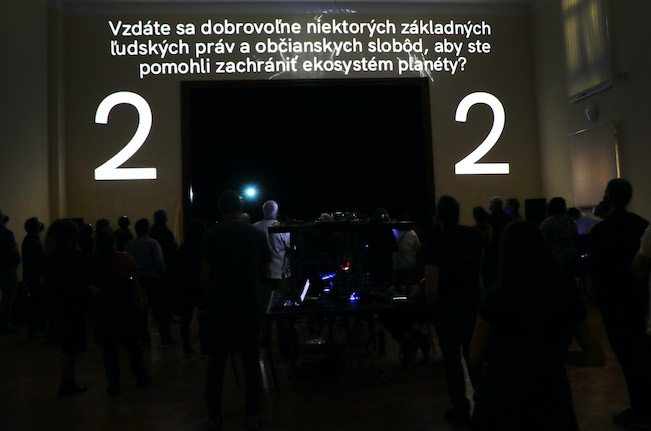

Grass Is Green docu-fiction presents an ambitious political plan to solve the ecological crisis.

What will convince our spoiled civilisation of a need to reformulate its dominant discourse and interrogates the relationship between the individual’s freedom and his or her responsibility – for society, for future generations, for the environment. Are there any solutions to the advancing eco crisis? Will they be private or – on the contrary – global political strategies? How willing and capable will we be in following the ‘moral law’ and how far will its limits be displaced?

One of many definitions is as follows: ‘Morality is expressed in the virtues of the individual who in judging and acting aims for the good, and can therefore distinguish the good from the evil.’ Morality is subjective, good and evil can be interpreted in numerous ways – especially given temporal distance, at which we often stamp something as either good or bad. But according to certain theories, morality is objectively tied to a specific period, time, space, that is to say the culture in which we exist.

When we begin musing about a new morality, it might be appropriate to first reflect on the new society that generates a new culture. What will the new society be like – if indeed there is one? Will the struggle for survival cease or only really begin?

In Grass Is Green, the publlic creates - via an interactive tool, following our questions - new Ten Commandments, more or less serious or paradoxical.

Our morality revolves around us. If apocalyptic predictions do come true, even partly, then we are en route to a dystopia rather than some utopian miracle, and the ‘moral law in us’ will be tested in due time. We are the only species that destroys its own habitat, and with it also the habitats of countless other animal species. Our vision could be of a society where anthropocentrism ceases to be a general filter in our worldview.

According to certain scientists, we are already witnessing global collapse. Some say we need to deepen our reverence for nature and mutual solidarity, others suggest we engage in esotericism and a new religion that would invest novel meaning in the existence of a society dependent on an enormous consumption of energy and boundless consumerism. Others believe in the aid of technology (although, already in 1865, British economist and logician W. S. Jevons described a paradox whereby an increase of efficiency in the use of a resource leads to an increase in the rate it is consumed, meaning technological advancement does not lead to lesser consumption).

However, many are of the opinion all these are but naïve and utopian revelries. Even if we succeeded in recalibrating our system, over time we would revert to exploiting resources to secure our existence at the expense of all other of the ecosystem’s elements. This pattern of behaviour is simply the basic precondition of life. The relative stability of the ecosystem ends where resources turn scarce.

‘If people were to disappear, who else would care but us?’ French botanist and ardent nature protector Francis Hallé was once asked. He thought it a brutal but completely justified question. But when trees disappear, so will people. As Polish philosopher Henryk Skolimowski writes, democracy is no longer sufficient, we need ecocracy as a form of government that respects the natural system in its entirety.